William Iveson Croome (1891–1967) – his work for the care of churches

By Jonathan MacKechnie-Jarvis

This article is an edited version of the Croome Lecture delivered in Cirencester on 15 February 1993 and published in Cirencester Miscellany no 3, 1996, pp.13-31.

Will Croome was closely associated with the work of the Gloucester Diocesan Advisory Committee for more than 40 years, and his direct influence can be seen in churches all around the diocese, but above all at his beloved church of North Cerney. Croome also worked tirelessly in the national arena, and this article shows the importance of his pioneering work in many developments in the care and conservation of churches. In presenting the lecture, the author was Assistant Secretary of the Diocese of Gloucester, and since 1986 had been Secretary of the Diocesan Advisory Committee.

Will Croome was born in 1891. His ancestors had lived in and around Cirencester since at least 1588. His great-uncle, who lived at Cerney House, was killed in a hunting accident, and since he had no issue, the estate passed to Croome’s father, Thomas Lancelot Croome. Alas, another accident took place, in which Croome’s father was thrown from a gig, near Perrotts Brook. He was left a hopeless invalid and died when Croome was four.

Will was the only child. His mother could not afford to stay on at Cerney House and moved with Will to Weston-super-Mare. They did not by any means lose touch with Cerney: there were regular visits to Bagendon House to stay with Mrs Capel Croome, widow of another of Will’s great-uncles.

On these visits Croome came into contact with Canon Peter Goldsmith Medd, then Rector of North Cerney. Croome admired Medd’s learning and antiquarian interests; moreover, Medds’s son Henry was the same age as Croome and a strong friendship developed. One day, not long before he died, Canon Medd had a serious talk with Croome, the two of them sitting in the south transept in North Cerney church. Croome was then 16. Medd spoke to him of the responsibility he would have when he came of age and inherited Cerney House, and in particular the responsibility he would have for the church. The incident impressed Croome deeply. He spoke of it many times to Canon James Turner, who was to be the last rector at Cerney, and who recorded it in his notes after Croome’s death.

Croome was educated at Malvern and went on to Oxford where he read Modern History at New College. In 1912, on coming of age, he assumed responsibility for the estate and received, among other things, the key to the family vault, below the south transept where he and Medd had had their talk. It is clear that by then he already had a mature and deep interest in church art and architecture, for he flung himself into a major work of repairing and beautifying the south transept, or the Croome aisle as it was then called, as a memorial to his late father. This, in itself a remarkable venture for one so young, was but the first phase of a lifetime’s work of benefaction to North Cerney church to which we shall return in the final section of this article.

Good companions

The gradual transformation of North Cerney church was made possible by the happy coming together of three people. The young Croome was one; the other two were Martin de la Hey and Charles Eden. De la Hey was Canon Medd’s successor as rector of North Cerney. Like Medd, he was distinguished academically, and had taken a First at Oxford. He quickly became fired with enthusiasm for improving what was a mercifully unrestored but drab and dark church. Eden was an architect friend from Oxford days, first employed by de la Hey on the parsonage but soon turning his attention to the church. Eden was thus the natural person for Croome to consult over his plans for the south transept. Both he and de la Hey also quickly became close friends and mentors of Croome.

Croome’s Sunbeam at Lechlade, 31 July 1929. Croome is on the right; Charles Eden is sitting on the running board. Croome’s mother is in the car with his aunt between them (courtesy Cyril Mills)

Eden had been a pupil of Butterfield and Bodley, but he owed his architectural mastery to his own wide observation and sketching of every possible detail. Writing in 1960, Croome bemoaned the comparative sparseness of such learning in the contemporary architectural profession:

“These architects do not have a tithe of the lore possessed by the older generation. They do not have time to travel, and soak themselves in the great works of the past; gain a wide knowledge of the varying ways in which subjects were presented, problems tackled, over the centuries; they have no theological, liturgical, or often even iconographical stores to draw upon.

I have always quoted dear Charlie Eden, because I knew him well. When we were at Orta, on that lake, a great traditional centre of ‘smithing’, he would not only draw lovely grille after grille in the Sacro Monte chapels; but poke into all the smith’s shops; talk to them, learn why they favoured certain patterns or scrolls as adding to the strength as well as to the decorative effect, etc, etc. And it all went into any ironwork he had to design. It was the same with textiles: his great cronies were Mary Davies (Mrs Antrobus) and Sister Anna Mary of the Bethany Sisters. From them he learnt all the dodges; the appropriate stitches for certain effects; the right way to arrange appliques, etc; and so all his designs for the frontal and vestments etc: not only worked out excellently, but generally carried precise directions as to which stitching, the braids and cords, to be used in every portion. We see nothing like that now.”

Croome, de la Hey and Eden travelled widely abroad, sometimes in company with Eden’s friend Walter Tapper, surveyor to Westminster Abbey. They visited France and Italy, photographing, rummaging in antique shops and tramping the great cities and the remote country areas. Through his friendship with Eden, Tapper and others, Croome added immensely to his own grasp of architecture, the Arts and Crafts, and of the liturgy to which these things were, for him and Eden, always subservient. This mass of learning and experience underpinned Croome’s huge contribution to the Care of Churches movement, which was to involve him so deeply from 1919 onwards.

Effects of the Great War

Alas, the Great War was soon to shatter the ordered existence of Croome’s world – indeed nothing would be the same again. Having very poor eyesight, combat duties were impossible for Croome and he served instead in the Medical Corps. He spent the war as Registrar of Wounded at the Southern General Hospital, engaged in the harrowing work of recording information and, very often, the dying requests of the appallingly mutilated casualties who were being brought in. The effect on someone without medical training, and with a fairly sheltered and academic background, can only be left to the imagination.

It was surely in an attempt to exorcise the ghastly shadow of what he had experienced that after the war he espoused the cause of the mentally ill, and became closely involved with the rehabilitation of offenders. The wisdom and understanding he brought to the latter work, as well as his many years on the Bench, must have been deepened by the experiences he had passed through.

Indeed, Croome had many interests and activities in addition to his work for the care of churches. He was a governor and lay Chairman of the Barnwood Mental Hospital; for 20 years Chairman of the County Probation Service; and for the same period Chairman of Governors at the Cotswold Approved School at Ashton Keynes. The Barnwood Mental Hospital work involved anything up to a full day each week, and he took a deep interest in the welfare of the patients, always touring the wards, and getting to know the long-term patients extremely well. Like his grandfather before him, he was a Magistrate, and served faithfully on the Bench until his 75th birthday, as well as chairing the County Magistrates Courts Committee and the Lord Chancellor’s Advisory Committee. The list is endless.

Fortunately, Croome inherited sufficient wealth to be able to devote himself entirely to those causes that were close to his heart. Apart from this, he never married, and this naturally allowed him a greater degree of freedom and the time to concentrate on his many activities. Nevertheless it is still astonishing that one man could have undertaken so much simultaneously for so long. Our astonishment continues to grow as we trace the gradual snowballing of his church work, for which he is best remembered.

The Care of Churches movement

At this point we need to say a word about the evolution of the Care of Churches movement, with which Croome was so closely involved from the outset. We must go back briefly to the mid-to-late 19th century, the height of the restoration mania, when huge numbers of churches were enlarged, demolished, rebuilt or restored, often being mutilated irreversibly in the process. The motives for restoration were numerous but above all the views of the Ecclesiological Society were of great influence in promoting the belief that anything later than 14th-century Gothic was decadent and should be conjecturally rebuilt to conform. There was widespread destruction of ancient features and textures, perpetrated even by architects of repute.

Amazing as it may seem, there was in those days no effective means of averting such disasters. The supposed system of ‘control’, which we still have today, was known as the Faculty Jurisdiction. Today it works; a hundred years ago it did not have a chance.

A faculty is a licence, issued by the Diocesan Chancellor on behalf of the Bishop, which is needed before carrying out works to a church. The system is an ancient one, going back to at least the 13th century. The problems a hundred years ago were twofold. Firstly, in those days you could only object to a faculty if you had a legal interest in the parish church: if you were a parishioner, a patron or a pew holder, for instance. This ruled out many who may have had a genuine interest in the well-being of the building in question, but who lacked a legal locus standi.

Secondly, and worse still, the Chancellors were appointed for their knowledge and experience of ecclesiastical law – as indeed they still are – and were unlikely to have more than a passing knowledge of matters of architecture, archaeology, art or history. Thus their ability to judge whether or not a faculty should be granted to restore or enlarge a church, let us say, could only be based on legalistic grounds, with little if any weight being given to the appropriateness of the work.

By the late 19th century, public concern was growing at the widespread restoration of churches, and the absence of proper control. A great landmark was the founding by William Morris in 1877 of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB). This was the first organisation specifically dedicated to stopping unnecessary destruction of ancient fabric. Some of its first committee members were churchmen and in its early years much of the Society’s work was to do with church restoration. Among its first victories we can include Lechlade, Coln St Denys, Malmesbury Abbey and the south porch of Cirencester – all cases where SPAB principles of repair were adopted and found both workable and economical, usually after a struggle against local opinion or vested interest.

By the early years of this century there was a substantial weight of informed opinion in favour of legal protection for ancient buildings. A bill was drafted – the Ancient Monuments Bill 1913 – which would have included church buildings under the law’s protection. Consternation among clergy and laity alike! Then, as now, the argument was that churches were places of worship, not museums or monuments, and should be left untrammelled by restriction. It was argued that the Church already had its own system of control – through faculties – and that the desired protection could be achieved by improvement and reinforcement of that system.

This argument won the day and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson, gave an historic undertaking in the House of Lords that the matter would be attended to, in return for which churches were duly excluded from the Bill. This began what is known as the ‘ecclesiastical exemption’ from historic buildings legislation.

A high-level commission was set up to examine how the system could be improved. The key recommendation was that, in each diocese, an honorary advisory board should be constituted to assist the Chancellor in architectural, archaeological, historical and artistic matters. This was the recommendation that transformed the faculty system from a toothless archaism into a potent means not only of preventing unworthy or damaging work to churches but, as we shall see, of encouraging best practice in all matters relating to the proper understanding of their use and care. Croome was to play the fullest part in this work for nearly 50 years.

By the time the commission’s recommendations were published, Britain was at war and the scheme had to be shelved. However, and perhaps ironically, it was the war itself that made a start on such a scheme imperative, by virtue of what became a tidal wave of applications for memorials of all descriptions – many of them ill-considered and unsuited for their surroundings.

Accordingly, the Advisory Committee idea was swung into action, the first committees dealing with war memorials only, although by 1920 or 1921 most were dealing with all faculty applications as had originally been intended. Oxford was the first committee, in 1916, followed quickly by others including Gloucester and Bath & Wells in 1919.

Local arrangements in Gloucestershire

The early days of the Gloucester Diocesan Advisory Committee (DAC) are quite an interesting study. It had something of a head start on account of the remarkable circle of artists and craftsmen centred especially around the Sapperton area. There were strong connections with the Arts and Crafts Movement and with the SPAB. It is perhaps not surprising that such people as Ernest Gimson, Sidney Barnsley and Norman Jewson were soon recruited. Time does not allow me to expand on the early battles and dramas, though the full story is told in my short History of the Gloucester DAC. However, a look at some of the results of the DAC’s work will show what it was seeking to achieve.

The flood of war memorial applications was usually for machine-finished brass tablets, with treacly enamel infill to the lettering. Where possible, the committee urged the use of English stone, and lettering designed and cut by competent artists such as Eric Gill, Randoll Blacking or Frederick Griggs.

For furnishing it was a case of encouraging appropriate purpose-designed articles rather than off-the-peg stuff from a church furnisher’s catalogue. Then as now, the cost was seldom the problem; it was rather the resistance to the interference of a committee, to the deflection from the pre-conceived plan.

Croome became involved in this embryonic cause, the Care of Churches movement, through Francis Eeles. To a large extent, Eeles was the father of the movement as it now exists. Working from a room at the Victoria & Albert Museum, and with practically zero in the way of funding, by sheer effort and enthusiasm he coaxed into life the first DACs and a national co-ordinating body known at first as the Central Council for the Care of Churches. He was an active member of no fewer than nine DACs, including Bath & Wells, Canterbury, Gloucester, Oxford, Rochester, Salisbury, St Albans and Winchester. Recruitment, encouragement and co-ordination was his role above all. At Bath & Wells Eeles persuaded Croome to act as the first honorary secretary, Croome then living at Weston-super-Mare. Writing in the 1960s, Croome described his initiation thus: ‘captured by Francis Eeles, rather reluctantly; little guessing what it really portended’.

Croome was Secretary of Bath & Wells DAC for five years until he moved to Bagendon, whereupon he joined Gloucester DAC as a member, though remaining a member of Bath & Wells for three more years. Today I doubt if there are many who would cheerfully serve on more than one DAC, each with a monthly meeting, site visits in-between and designs and paperwork to examine and report on. That he did so is typical of the indefatigable Croome. In 1927 his real work for Gloucester DAC commenced when he became honorary secretary, a post that he only gave up in 1950 to become Chairman, in which office he remained until his death in 1967.

The work-load increases

Croome’s work for the care of churches snowballed as the movement broadened and developed. As we have seen, the committees started work dealing with the war memorials problem and quickly progressed to advising on general faculty work, as had originally been intended. There was also an educational role – a desire to promote high standards of work and the intelligent use of church buildings. The Central Council for the Care of Churches was in the forefront of this, but it was a job that could only be effective if the diocesan committees were energetic and responsive to parish needs.

As secretary of Gloucester DAC, Croome soon established his own style, tirelessly visiting, encouraging and advising. His approach had a refreshing practicality about it, and was intended to be of maximum help to the parishes and their architects. Before long there were few churches in the diocese where he had not been directly involved. The result of his advice can often be seen today – the decluttering of the chancel, a well-designed memorial or some new furnishings perhaps. The Croome touch, we may call it.

Before long he pioneered lantern lectures on the care of churches, going round to theological colleges to speak to ordinands about their future responsibilities. Here is a typical piece of Croome, taken from one of his booklets:

“Keep an eye on the down-pipes and on the soak-away or drain into which they discharge at the foot. The only useful time to watch these (there is no shrinking this unpleasant truth) is on a really wet day, under mackintosh or umbrella, to make sure that there is no obstruction in them.”

He also stressed the importance of correct materials: “To the present-day builder, Cement is almost the staff of life, his remedy for a dozen ills. But only in special circumstances, and then only under skilled control, ought a cement bag ever to be carried inside the churchyard of one of our Gloucestershire stone churches.”

Just one small example might be quoted as evidence of his constant concern for practical detail in dealing with casework. The priest’s desk at Little Barrington was a typical minor refurnishing project around the time of the Second World War, designed by his old friend Harry Medd, son of Canon Peter Medd whose words to Croome in North Cerney church had so influenced him. Here is Croome’s advice, writing as DAC Secretary to the Chancellor:

“The Committee that examined these designs at their July meeting before the Petition was prepared advises the Chancellor to sanction the plan for a new Priest’s Stall and Reading Desk by Mr Medd.

“They have secured his and the Donor’s agreement to three very small changes, which in no way alter the general design, which they thought excellent. These changes are:

- Both the seat and the back of the stall will be slightly canted to avoid discomfort. A flat seat, with a near perpendicular back, is very uncomfortable after the first few minutes.

- The book-rest on the stall will have a flush top (with of course the rest at the foot of the slope to catch the Books) in place of the sunken panel shown. This is to make convenient use of a Book of any size; the sunk panel only holding books no longer than eight inches.

“These have not been the subject of a new drawing, to save the considerable expense of preparing this; which perhaps the Chancellor will excuse.”

When he took over as secretary of Gloucester DAC, Croome had been living at Bagendon House for some three years. The estate was fairly impressive, with a good handful of staff, but above all the Mills, father and son, who were hugely important to Croome in all he did. As chauffeur and factotum, Cyril Mills succeeded his father and became known to everyone with whom Croome had contact. Somewhat earlier Croome had set up for Cyril and his father a garage which you can still see at Perrotts Brook, although the old pumps and sign have long since gone. With typical attention to detail, Croome had had a tall oak post and tavern sign designed by Charles Eden. For a man who never drove, Croome owned a wonderful succession of cars, which feature prominently in the photo albums he methodically compiled.

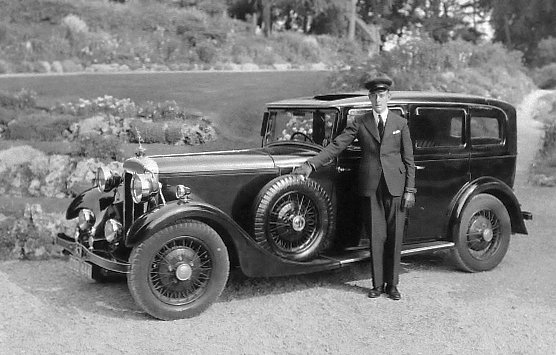

Cyril Mills, photographed in August 1937 at Bagendon House, with Croome’s Daimler (courtesy Cyril Mills)

Croome devoted his whole life and means to the work, not only of the church but also of his many voluntary welfare activities. Without doubt he could not have done it all without transport of a comfortable and reliable nature. Within the restrictions of Gloucestershire’s roads, it also needed to be fast, given the huge number of meetings and the distances involved. Not for nothing was Cyril Mills known to all and sundry as the ‘flying chauffeur’.

Undoubtedly Croome was what we now call a workaholic, who rarely relaxed or let up. He never even had a part-time secretary , which would seem to be an obvious requirement with his volume of correspondence. Instead he laboriously typed his own letters, often working ‘til gone midnight or, indeed, right through Christmas Day, as his diaries reveal. Even on holiday – a favourite retreat being Chagford, near Dartmoor – it would be non-stop photography and long day trips to places of interest – including a good few churches no doubt.

Croome was an inveterate correspondent and fortunately a mass of his letters have survived in one way or another and they are a treasure trove of information and anecdote. It is perhaps surprising to relate that many of them, confidential to the recipients, are still potential dynamite, as he was forthright in what he wrote about people – by no means all of whom have passed on! One day a fine selection of his letters could be published, but a few more years must roll.

Because he never had to earn a living it is tempting to think of Croome as comfortably off, and free from worries about income or housekeeping. In fact these things became progressively harder, and after the Second World War it was clear that Bagendon was in a poor state and beyond his means to maintain. He therefore had to sell up and in 1954 moved into Barton Mill House, in Cirencester, having in the process parted with a great deal of cherished furniture and books.

The Second World War must have been a trying and dreary period for Croome. Progress in the Care of Churches movement came to a halt and everyone had to brace themselves for the incalculable results of air raids. Art treasures has to be evacuated from vulnerable churches, with great potential for damage or loss in the process. In Gloucestershire the DAC found its work made harder by petrol rationing and, in any case, much repair or improvement work was put on ice for the duration. Meetings became few and far between.

You will recall that I spoke of the Central Council for the Care of Churches, set up to act as the co-ordinating body for DACs. It had, and still has, an important role to play not only in giving a second opinion in difficult cases but in seeking technical advice on common problems affecting church buildings, rather than leaving 43 different DACs each to work out its own solution. Croome sat on the Central Council from about 1927 onwards. After the war his influence and work there increased dramatically.

If the war created problems for the Gloucester DAC, the Central Council fared even worse. Its office was evacuated to Dunster, in Somerset, and its work of co-ordination and communication was devastated. At that time its chairman was Dean Cranage of Norwich, a great man but no longer able to take hold of the huge problems and opportunities facing the care of churches system. After the war came his overdue retirement and, in due course, the appointment as Chairman and Vice-Chairman respectively of that remarkable Gloucestershire duo, namely Dean Seiriol Evans and Will Croome. In many ways they were contrasting figures – Evans a powerful influential man, a good figurehead; Croome a doer and an enabler, with already 30 years’ experience of caring for churches. Despite many differences, they were a fine team, especially in the national arena.

The conservation challenge

One of the first priorities was that of conservation. There was a great need for a scientific approach in all branches of the work, perhaps above all in wall paintings. Disastrous pre-war restoration methods, involving the misguided application of wax, hairnets and other alien stuff, needed to be rethought and reversed. A better understanding was needed of ways of consolidating ancient plaster without hindering evaporation of moisture. If sealed in, as with the pre-war hard waxes, the plaster could blow off by the continuing action of dampness, present in every ancient wall.

Another need was to be able to uncover painting hidden behind limewash or plaster and often to unscramble superimposed layers of wall paintings of different date. Seemingly miraculous feats are now possible by experienced conservators, as for example in the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre in Winchester Cathedral, conserved flake by flake with staggering expertise.

Croome managed to assemble a wall painting committee for the Central Council, comprising senior individuals from the National Gallery, the British Museum, the Courtauld Institute and the Ministry of Works, and got them – not without difficulty – to tackle the problem under his chairmanship. He also got the funds from the Pilgrim Trust, without which little could have been achieved. This enabled members to travel on the continent to see what could be done, and to invite continental conservators to England. Further funding enabled adaptation of the appropriate techniques, and direct grant-aiding of long overdue work. In this diocese one could mention Baunton, Kempley St Mary and Stoke Orchard, at which latter church phases of the work are still to be completed.

In due course Croome persuaded the same working party to turn its attention to paintings on woodwork – for example, medieval rood screens – and finally to glass conservation. Here his skill as a chairman and diplomat were tested as never before as he worked and persuaded and manoeuvred his way towards a centre for glass conservation at York – the York Glaziers Trust as it is now known.

This is the briefest summary of Croome’s initiative in the specialist field of conservation – wall painting, paintings on wood and stained glass. But what of run of the mill work, the plight of the legions of country churches with their constant need for maintenance and repair? It must be borne in mind that in many cases little major work had been done since the 19th-century restoration campaigns. The Second World War had brought about a moratorium on repair which, due to acute shortages of labour and materials, had extended well into the post-war years. Now, in the late 40s and 50s, the desperate appeals were coming in for help, and a system was needed to put them into some sort of priority for assistance and to monitor their likely needs for the future.

Croome was involved to the hilt in a two-pronged attack on these problems. The first stage was the setting up of the Historic Churches Preservation Trust (HCPT), again with the generous help of the Pilgrim Trust who, truth to tell, were glad to see a system which could make sense of the constant string of desperate parish appeals that had been queueing at its own door. Croome was a founder-trustee of the HCPT and soon became chairman of its grants committee. This was a chairmanship that he tackled with typical thoroughness, acquainting himself each time with all the cases on a rapidly lengthening list of applicant churches.

The other pressing need, that of an early warning system, was answered by the introduction of the Inspection of Churches Measure in 1955. Here again Croome was in on the ground floor, being heavily involved in the consultations and discussions, formulating what was then a revolutionary new requirement on the parishes. The resulting system was a winner and has contributed incalculably to the dramatic improvement in maintenance standards of most of our churches since then. In essence it provides that each church must be inspected every five years by a competent architect, whose report goes not only to the parish but to the archdeacon and diocesan office as well. Inspection is not the same as repair, it is true, but it is a vital prerequisite. In short, the system has worked.

A role with cathedrals

So far we have dealt almost exclusively with parish churches, cathedrals being exempt from faculty jurisdiction. They are, however, by no means exempt from public concern, nor indeed from controversy, for they are so much in the public eye and jealously regarded by all and sundry as ‘our heritage’. We have recently seen a strengthening of accountability in the new cathedral fabric committees, which started work in 1991, but before 1950 there was nothing, and the Deans and Chapters enjoyed almost total freedom. In 1950, a start was made with the establishment of the Cathedrals Advisory Committee to act as a voluntary consultative body for Deans and Chapters. Once again Croome was to be involved heavily, first as vice chairman but soon as chairman.

In this work, he greatly added to his already colossal burden. The Cathedral Advisory Committee was at first regarded with deep suspicion and hostility by the cathedrals, and throughout its existence was hampered by being a voluntary reference point only. Moreover the workload was heavy and often controversial. Meetings became monthly and site visits, which could be anywhere from Truro to Newcastle, were inevitably required. Meanwhile, Deans and Chapters outdid each other in acts of astonishing folly – destruction of screens, removal of stained glass and so on – incurring the wrath of the conservation lobby the while. Croome’s letters often tell of the strain that this imposed, party as he was to a mass of confidential and sensitive information, to lobbying, to endless pressures and counter-pressures. Yet he was ideally suited to carry out the task, having the widest knowledge, and commanding the widest respect and influence, and being so totally committed both to the welfare of the buildings and to the faith of the church for which they existed.

You may deduce from this that Croome was now involved in a relentless round of meetings all over the country, His hectic timetable was often revealed in letters to his friend and colleague, Judith Scott, who was then Secretary of the Council for the Care of Churches. His commitments in London frequently meant that he had to stay there for several days at a time, usually staying at St Ermin’s Hotel in Westminster. This did not mean, however, that his work in Gloucestershire, especially the Diocesan Advisory Committee, had slackened, or that others were now taking the strain. When Croome succeeded to the chair of the Gloucester DAC in 1950, the immediate problem was to find an effective successor as honorary secretary. With a monthly meeting brim full of casework, ranging from the routine to the downright tricky, with agendas and minutes to prepare and the endless correspondence and phone calls, it was perhaps hardly surprising that the stampede for the post was not great. For a while the job was done by James Turner, Croome’s rector at North Cerney, but alas his health was not good, and Croome had to take the work back himself for a while. To quote from a letter to the Diocesan Secretary, P J Davies:

“Turner’s prolonged illness is a grave difficulty: the letters of this Committee can only be drafted and sent by somebody who grasps and understands the issues, and there is no other member able to give the time. But it is a heavy burden on me and I fear the Parishes will suffer.”

The job was later done by Captain Stewart Gracie, who coped well for nearly a decade, but even then Croome still had to handle the heaviest and trickiest letters and reports. Croome’s own health was not always good – here he is writing to David Verey:

“I simply cannot get 24 hours peace in which to be ill. I collapsed on Thursday, while attending the dedication of the Dr Eeles memorial at Selworthy in Somerset: came back to bed: but had to rise on Saturday morning to expound N Cerney Church to 60 students. The Parson was still ill, nobody could do it for me, so it had to be tackled.”

It is true that the really tough work of church re-ordering – the provision of coffee facilities, loos and meeting places, which today so exasperates the conservation lobby, had yet to arrive in force. Nevertheless Croome had to steer the DAC through at least one major trial run for this type of thing, namely the Northleach case in 1962–3. Here we have a thorough liturgical re-ordering that is now rather an interesting period piece of the 1960s, adding to the interest of this jewel among Cotswold churches. It was a major scheme, promoted with much zeal in the parish, and involved a lot of serious complications, such as the moving of the ancient brasses. As it evolved, the project took a huge amount of DAC time, improvements and alterations being argued and conceded. The eventual scheme was successful in its aims, although by today’s standards it would be regarded as lacking flexibility, being based largely on fixed arrangements. Poor Croome had not only to steer the controversial scheme through to a conclusion, he also took it upon himself to compile a ten-page report for the Registrar, ending as follows:

“The Committee wishes to tell the Chancellor that they regard this as perhaps the most important matter to have come before them; that they have devoted the most anxious thought and care before making their recommendations to him; and that they have secured many modifications which they hope he may feel leave the final plan as a rational and acceptable method of adapting an ancient and splendid church to modern needs of worship.”

Croome with Philippa Buckton on the St Edmondsbury DAC, examining a model of St Aldate’s Church, Gloucester, 1964 (courtesy Miss G Scott)

The 1950s and 1960s also saw a good deal of work on new churches, often replacing pre-war mission halls that had come to the end of their life. A good example is the space-age St Aldate’s, Gloucester. It is a handsome, innovative church, though unfortunately not a success environmentally, being difficult to heat and ventilate adequately, and very noisy due to the traffic on the ring road. Both in Gloucester DAC, and nationally through the Council for the Care of Churches, Croome remained fully in touch with a rapidly changing church and society, reflected, of course, in the style and construction of these new churches and – as at Northleach – in a demand for change and adaptation in old buildings.

I hope that by now I have sketched something of the breadth and scale of Croome’s work, from its beginning in 1919 on the Bath & Wells Memorials Committee, through his long Secretaryship of the Gloucester DAC, and then its mushrooming after the war at national level in so many ways – the Central Council, the Cathedrals Advisory Committee, the wall paintings, the glass, the Historic Churches Preservation Trust and many more things besides. As one who is involved professionally in the care of churches system today, it is fascinating to observe how many of the most successful developments were pioneered by Croome.

So often he was involved in the first discussions and consultations, perhaps knowing that he would not live to see the full fruition, but lobbying, discussing, enabling, overcoming inertia in committees and councils. For example his involvement in the growing problem of redundant churches – paving the way for the Pastoral Measure and for the Redundant Churches Fund, both of which have enabled dignified solutions to the problem of unwanted churches, but both of which came along only after his death.

North Cerney church (courtesy National Churches Trust, photo Brian Chadwick)

The interior of North Cerney church, a classic view by Will Croome taken in 1940 (courtesy Jonathan MacKechnie-Jarvis)

North Cerney Church

I have left till last that which was closest to his heart, namely North Cerney church. When we last considered Cerney it was around the time of the Great War and I described how Croome, aided by de la Hey and Charles Eden, reordered the south transept as a memorial to his father. This was the first project in 50 years of work and benefaction by Croome and others. North Cerney became a living model of the highest standard of repair, of furnishing and textiles. After Eden’s death, other architects were involved, such as Robert Potter and Stephen Dykes-Bower.

While Croome himself was the largest donor, he influenced many others – not only amongst his relations, but from all over the parish – to do likewise. Luckily, he recorded everything in great detail on his list of gifts and names of donors, and we can thus be sure that vital information does not, as so easily happens, slip out of mind. Outstanding among these benefactions is the dramatic rood loft of 1925, designed by Eden. Made of local oak, it was carved by William Smith and constructed by Henry Mason, the Churchwarden. The figures are Italian: the central figure is 17th-century work, and was chanced upon by de la Hey in an antique shop in Italy. The work was paid for by Mrs de la Hey as a memorial to the men of Cerney who fell during the Great War.

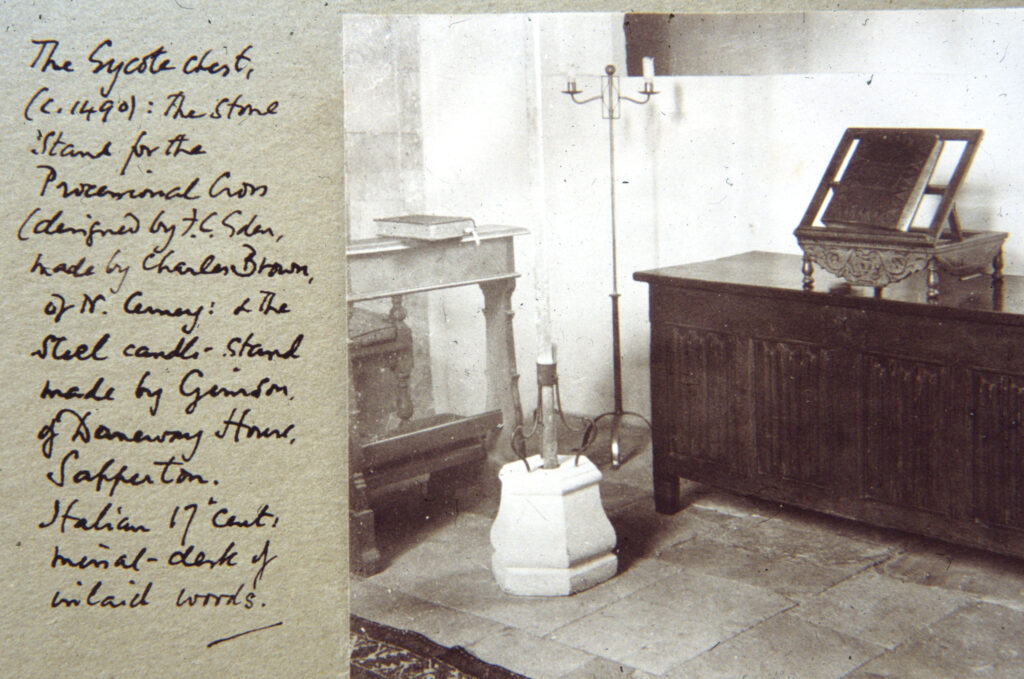

North Cerney: a page from the photographic log book. This illustrates the high standard of antique and contemporary furniture and fittings gradually amassed and catalogued for the church by Croome (courtesy: Revd Howard Cocks)

Gradually, many projects of enrichment and improvement were commissioned, and Croome’s touch can be seen everywhere in the church. The full story is told in his exemplary photographic log book, a priceless and painstaking record of the stage by stage transformation. Long may the guardians of this lovely place guard it from decay and from ill-advised change.

If one wonders what gave Will Croome his amazing stamina for church work, what kept him going through all the exasperations peculiar to clergy and their PCCs, one has only to read his own accounts, in letters and his diaries, of his work as sacristan and server at North Cerney. Here was the real heart of the thing. Faith and worship to him were natural, inseparable and deeply rooted. The rigorous discipline of his devotional life remained unshaken to the end, though he did mention in one letter having for the first time in his life drunk a cup of coffee to fortify himself before a communion service.

Croome did not wind down to any real extent – he died very much in harness as I am sure he intended. He had retired as a magistrate the previous November on reaching his 75th birthday, and a few years earlier had relinquished some of his other Gloucestershire duties, such as those at Barnwood Hospital and the Cotswold Approved School. He remained Chairman of the Gloucester DAC to the end, however, and did not in any way let up with the national bodies, the Council for the Care of Churches, and the Cathedral Advisory Committee – despite warnings from his doctor about the pace he was setting himself. In a characteristic letter to Judith Scott, he gives us an idea of the pressure of his engagements – and this was two months before the end:

“My train got in at 6.30; Cyril was on the platform to guide me to the car among the 120-odd parked there. We got here at 6.40 and I hurled off one set of clothes and threw on the others; and I reached the Bingham Hall exactly as the Toastmaster chivvied the company into dinner. The ‘Distinguished Visitors’ were kept back to enter in procession when the mixed multitude were seated; so I nicked into the queue as it entered the doorway. I was not ‘up‘ till 10.30pm, the Councillor who proposed our toast taking 29 minutes to do so! Seeing the universal weariness, I packed such comment as I had got together into 9 minutes; got home just after 11.30 and fairly tumbled into bed.”

He was setting out on 21 April 1967 for a further round of meetings in London when he suffered a heart attack followed by a stroke a few days later. Mercifully he was spared the misery of lingering illness and died peacefully on 29 April. He was buried in the churchyard of his beloved North Cerney.

North Cerney churchyard cross, probably 14th century. Beyond is Church Cottage, built as a priest’s house, perhaps c.1470 (courtesy David Viner)

Will Croome’s memorial can be seen in the south transept at Cerney, a handsome plaque by John Skelton, who learned his craft under Eric Gill. Surely Croome would have approved the use of a limestone surround to soften the contrast between the slate and the limewashed wall. But if you seek a monument, look around, not only at the transformation of Cerney church, but at the development of the whole system, a whole ethos for the intelligent care of our priceless church buildings. That system, we can say with confidence, is continuing to develop and to flourish and to be put to the service of parishes and cathedrals alike. Long may it continue to uphold those high standards that Will Croome did so much to encourage and promote.

Notes, acknowledgements, and postscript

The author is indebted to Judith Scott and to Cyril Mills. Both have been very generous with recollections, letters and photographic material, and this article could not have been written without their help.

For a fuller account of the development of the Care of Churches system and the Gloucester DAC, see A History of the Gloucester Diocesan Advisory Committee 1919– 1992 (MacKechnie-Jarvis, 1992). This contains details of source material, much of which relates to the present article.

Postscript:

Two important studies have appeared since this lecture was published in Cirencester Miscellany: Canon James Turner The Rectors of North Cerney, the 700-year story of a Cotswold church and its clergy, published by Silverdart Ltd in 2006 (www.silverdart.co.uk)

Alec Hamilton, ‘Re-constructing the pre-Reformation church: Will Croome and F.C. Eden’s antiquarian ecclesiology at North Cerney, Gloucestershire’ in Ecclesiology Today (the Journal of the Ecclesiological Society), nos 55 & 56 for 2017, 123-148. See https://ecclsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ET-Issues-55-56-2017.pdf

July 2024