Image 2

Image 1

Image 3

Scholars not Saints: Alexander Neckham and the community of Canons at the Abbey of St Mary, Cirencester

As shown in the following NEWSLETTER Number 63: 2017. Abbey 900 in Cirencester

During 2017 Cirencester has been celebrating the 900th anniversary of the ‘King’s great work at Cirencester’ – thought to be the foundation of Cirencester Abbey in 1117. Via the Abbey 900 programme of events, many people have been attracted to the history of the Abbey of St Mary and discovered more about its buildings (virtually all now long gone), and the people who made up the abbey community of Canons and formed part of town life for over 400 years.

This issue is devoted to one important part of that story, the role of the Canons in scholarship, the significance of the abbey library and the key personalities in that story. Alan Welsford has been studying this subject for many years and was responsible for the idea of bringing Alexander Neckham further into the spotlight.

With museum staff he was instrumental in securing the loan of four precious manuscripts associated with Abbot Alexander Neckham, some of which once belonged to the abbey’s library, for a special display in the Corinium Museum from January-May 2017 as part of Abbey 900. This loan will certainly be remembered as one of the highlights of the Abbey 900 year of events.

Alan’s text used here has been developed from his blog on the Corinium Museum website accompanying the exhibition, with additional input from Dr Andrew Dunning describing the significance of the books on display. Its publication by the Society as its Newsletter for 2017 creates a permanent record of an important part of the story of Cirencester Abbey.

In summary: books were of great importance in monasteries such as the Augustinian Abbey of St. Mary in Cirencester.

The manuscripts were written out both by the Canons and by professional scribes and illuminators including Ralph de Pulham mentioned by name in one of them. Amongst the Canons, as the priests of the Abbey were called, there were scholars who built up a library of scholarly books which attracted an important medieval thinker to Cirencester in around 1200, Alexander Neckham (Neckam or Nequam). He was part of the 12th century Renaissance bringing new approaches to study, becoming Abbot at Cirencester in 1213. He died in 1217.

David Viner, Editor

[dviner@waitrose.com]

Illustrations, front cover

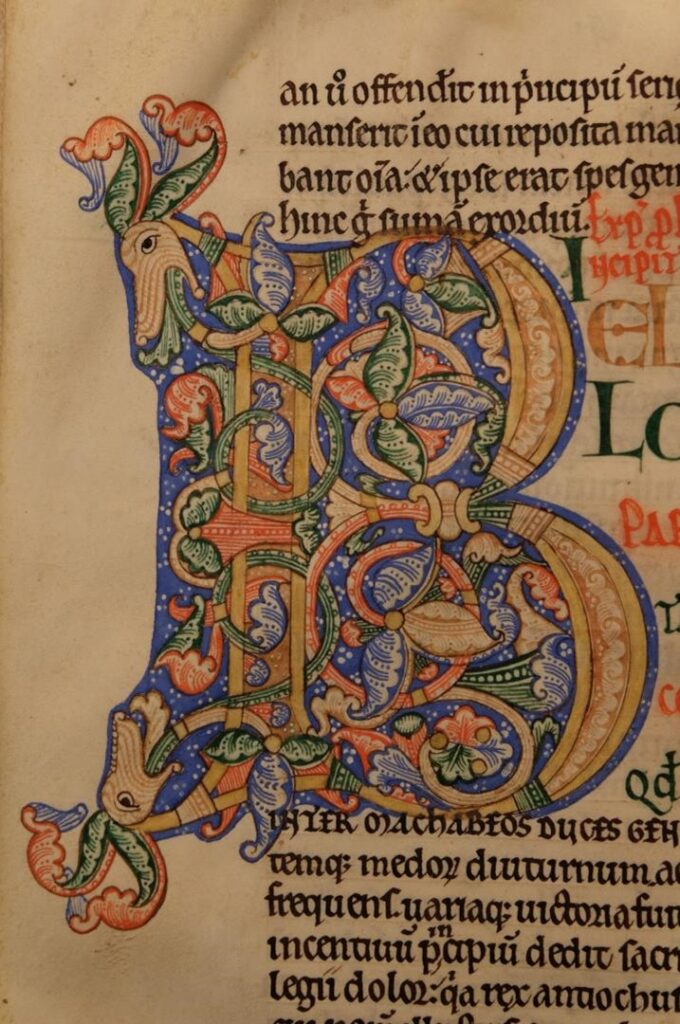

- Alexander Neckham, Glosses on the Psalter (Gloss super psalterium), Cirencester and Oxford, first quarter of the 13th century. Detail from MS. Bodl. 284, fol. 196r, Jacob wrestling with the angel, in the historiated initial for Psalm 81 (80), ‘Exultate Deo’. Courtesy The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

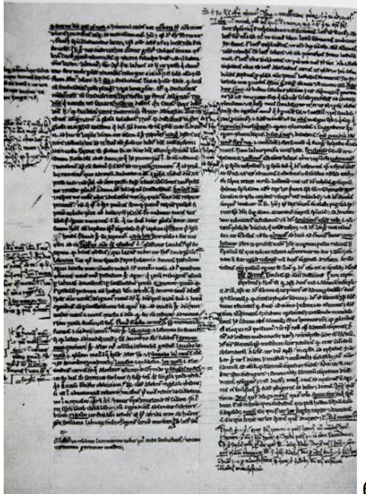

- A folio from Hereford Cathedral Library, copyright ref 0.1.6.

- Copy of work by Robert of Cricklade (courtesy Alan Welsford).

Scholars not Saints: Alexander Neckham and the community of Canons at the Abbey of St Mary, Cirencester

by Alan Welsford

Cirencester Abbey was founded by Henry I to replace the existing College of Secular Canons at Cirencester with a community of Augustinian Canons. Henry was following Papal preference in choosing the Augustinians to replace the resident secular Canons. The Augustinians differed from their predecessors in that they took the monastic vows of poverty, chastity and obedience: they were known as Canons Regular – that is living under regulation.

The Augustinian “Rule” was less clear than that of the Benedictines, being developed from the writings of St Augustine of Hippo (author of The City of God in the early 5th century) who made recommendations rather than strict rules for Christians living in community. Each Augustinian community of Canons Regular developed their own precise Rule – the one for Cirencester is not known.

It was sometime before any building began. The first dozen or so Canons arrived in 1130 or 1131 coming from Merton Priory in Surrey, probably using the Anglo-Saxon minster for their church. The foundations of this minster were discovered during the excavations of the Abbey site in the 1960s and revealed the largest yet known Anglo-Saxon church in England as well as extensive foundations of the Abbey church and buildings.

The first Abbot was Serlo whose abbacy lasted from 1130/1 until 1147. Serlo was probably Dean of Old Sarum and had previously been a Canon of the Augustinian Priory at Merton. The final consecration of the great Abbey church did not happen until 1176 in the presence of four bishops and King Henry II. Work continued for many years to complete the church and provide the full complement of conventual buildings – cloisters, refectory, dormitories, an Abbot’s House and, most importantly from our point of view here, a scriptorium and a library.

As did the Benedictines, the Canons maintained a daily round of religious services, the Opus Dei (The Work of God). These began at midnight with Matins and Lauds, Prime at 6am followed at 9am with Terce, then Sext at noon, None at 3pm, Vespers at 6pm and lastly Compline at bed-time, 9pm. These services, or Offices as they were known, were developed around the recital of the Psalms from the Bible.

The Abbey also had Missals for use at its daily Conventual High Mass which took place at the High Altar. There are few Missals remaining from medieval England, and none from Cirencester Abbey. At the Dissolution of the Abbey in 1539 anything of value was sequestered to the Crown. Missals and other liturgical books often had precious metals and gems set in their covers.

Whilst the Augustinian worship in their churches was very much like that of the great Benedictine Abbeys, in some other important ways their life differed. The monks of the Benedictine Order had a strong emphasis on “stability”, that is staying in their Abbey; they had laymen as well as priests in their community and were concerned with liturgical practice and spiritual development. The Augustinians by contrast were a community of priests only, who employed staff to care for the day to day work within the Abbey and had a concern for work in parishes, taking them outside their precincts.

At its foundation, the abbey was endowed with many parishes both close by and in more distant places and so had responsibilities for them. Cirencester was one of these and also Cheltenham. On exhibition in Corinium Museum is the tomb-stone from the grave of Walter, one of the Priests serving Cheltenham church who was a member of the Council of Cirencester Abbey though not a member of the community proper.

The Augustinians had a greater emphasis on scholarship than the Benedictines whose studies were directed to understanding received ideas and their implications for the spiritual and liturgical matters around which their lives were centred. Another difference was that the Augustinian life outside their Abbey brought the Canons into contact with changes in society stemming from economic developments and new intellectual stimulation. These two factors were to be of some consequence both to Cirencester Abbey and the Church more widely.

Little is known about the Canons who were at Cirencester beyond the Abbots whose roles in securing the influence of the Abbey locally, nationally and beyond are recorded from the Cartulary and documents preserved in national archives. Some Canons are known only as names which appear in the Ex Libris entries in manuscripts. However, there are some whose names and works established Cirencester Abbey as a monastery with formidable scholars. All were thinking and writing during the so-called Twelfth Century Renaissance of scholarship.

Canon Jocelyn

One of those scholars at Cirencester was Canon Jocelyn who was probably amongst the Canons of Merton whom Serlo chose to accompany him to Cirencester to set up the Abbey. In Hereford Cathedral Library is a collection of books which belonged to Canon Jocelyn known by its incipit or title: ‘While some are considering the theory of multiplication and division.’ Within this volume is Jocelyn’s copy of De Abaco (On the Abacus) by Gerlandus (c.1080).

It may be that Canon Jocelyn’s interest in numbers and calculation stemmed from the problems the Church had in determining the correct date for Easter Day – the compotus – and the use of number to elucidate theological issues. It was thought that 1x1x1=1 gave an intuitive understanding of the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. There are nine known medieval copies of Gerlandus; what is especially interesting about Jocelyn’s copy is that it contains a verse for remembering the “new” Hindu-Arabic numerals that we use today; and not only that: it is the only copy which includes “zipos” or zero, which has led to the claim that Jocelyn is the first person known by name to have understood the importance of zero in the new mathematics. At that time Cirencester was in the Diocese of Worcester which was a centre of Arabic studies translating Arabic and Greek texts into Latin.

Augustinian Canons had great freedom of movement and so we can wonder if Jocelyn met with other scholars in Worcester Priory (now the Cathedral).

Robert of Cricklade

Another scholar whose name we know from the earlier days of Cirencester Abbey was Robert of Cricklade. Educated in that town, Robert became a master in the Schools at Oxford which had emerged in the late 11th century, though not yet a University. He entered Cirencester Abbey before 1139 and whilst there wrote his De connubio Iacob (On the marriage of Jacob). What may have been his own copy survives in Hereford Cathedral Library (Ms P.iv.8.). This work is an allegory on the story of Jacob, one of the Patriarchs in the Old Testament. Robert was amongst the scholars who appreciated the need to examine the Bible in the light of the emerging Aristotelian approach of questioning received opinion.

He learned Hebrew which was important in another of his works amongst Cirencester manuscripts now in Hereford (O.iii.10): Homilie super Ezechielem (Homilies/Sermons on the Book Ezekiel) which shows his knowledge of Hebrew. But this was written after he had moved to be Prior of St. Frideswide in Oxford (now Christ Church). Dr Andrew Dunning draws attention to Robert’s insistence on the importance of scholarly writing.

Enter Alexander Neckham

Dunning also noted that even after Robert’s death (between 1174 and 1180), his work at Oxford and Cirencester inspired the work of the famous Alexander Neckham (1157–1217), who was born in St. Albans of aristocratic parents on the same day as Richard the Lionheart was born in Oxford. As was customary at that time, the Royal baby was immediately fostered onto a nursing mother – Alexander’s mother, Hodierna (it is probable that Hodierna Knoyle – now West Knoyle in Wiltshire – is connected to the family). Hodierna must have known the great Eleanor of Aquitaine.

There is evidence that Hodierna had favour with the Royal Family as she received a substantial pension from Henry I which was still being paid to her by King John. So it is reasonable to suppose that Alexander also had Royal favour, which was important when King John was levying severe taxes, including on Abbeys, to fund his conflicts with France: Cirencester Abbey seems to have been excused.

Neckham was educated at the school at St. Alban’s, founded in 948 and one of the oldest of all schools. Later he was himself a Master at St Alban’s and he also taught at Dunstable in Bedfordshire, which was under the control of St Alban’s Abbey. By 1180 he was in Paris, noted by R.W. Hunt as ‘at this time the goal of all students in the arts and theology.’

Alexander may have gone to Paris through the encouragement of a cleric or by St. Alban’s Abbey. At some point the young Alexander agreed with fellow students that they should eventually enter into monastic life. The received attitude to theological study was to interpret the Church’s teaching in the light of thought rather than observation. It was the re-discovery of the Greek classics via the Arab world and translations into Latin that stimulated the Twelfth Century Renaissance.

This movement followed Aristotle; Neckham calls him “the great, the most acute Aristotle, the most excellent philosopher, the guide, the head and honour of the world”. But Aristotle was a pagan and there is a hint that Neckham was uncertain of how the Church would react to this new approach and in his Commentary on Ecclesiastes he suggests that these books should be studied discreetly.

By 1185 Neckham had secured the post of Master at the school in St. Albans. To obtain this position he had written to Abbot Garinus who replied in a pun on Neckham’s name: Si bonus es uenias; si nequam, nequamquam : If you are a good man, come: if worthless, by no means.

Within five years Neckham became one of the first known lecturers in Oxford. There, he was probably a canon at St Frideswide’s Priory where Robert of Cricklade had been Prior. At this time, it was customary for Masters to refrain from lecturing on the Feast of the Conception of the Virgin Mary but Neckham did so, presumably showing an independence of thought on religious matters. Something occurred to change his behaviour if not his opinion as later he did stop lecturing on this feast day.

It was during this period in his life that he wrote two works revising fables: Novus Esopus (Aesop) and Novus Avianus (a Latin writer c 400 AD). In lessons on rhetoric schoolboys were required to analyse fables, give them a moral interpretation and create their own. One of Neckham’s own is included in his Novus Esopus. “A gnat settled on the horn of a bull, and sat there a long time. Just as he was about to fly off, he made a buzzing noise and enquired of the bull if he would like him to go. The bull replied, ‘I did not know you had come, and I shall not miss you when you go away’.”

It was also at this time that he wrote De nominibus utensilibus (On the names of useful things) for his students.

“Although Latin was widely used in twelfth- and thirteenth-century England, it was nobody’s native language.

Alexander’s volume offers an innovative approach to practical Latin, presenting the reader with descriptions of objects (the large text in the centre of the page) that might be found in everyday life, such as a kitchen, church, or ship. The extra space in between the lines allowed students to add glosses in their own language, usually Anglo-Norman French. The text was on the cutting edge of science, and includes the first description of the pivoted magnetic compass needle; it is also one of the only sources on 12th-century English cooking”. [Andrew Dunning]

Neckham at Cirencester

Alexander Neckham entered Cirencester Abbey between 1197 and 1202. Had he become tired of the need to attract scholars? Masters at the centres of higher learning needed entrepreneurial endeavour to earn their living: pupils brought fees. On the other hand, it was a common decision at that time to enter a monastery late in academic life to have time to consolidate one’s studies.

Some of his academic colleagues had tried to dissuade him from fulfilling his youthful pledge to enter a monastery, ‘but he became like a deaf man and heard not the sounds of the world.’ Peter of Blois, Archdeacon of London and one of his friends, congratulated him on his decision. However, we should not think of Alexander as a dour ascetic. He had a reputation for making jokes including practical jokes. When he was once asked to keep a sermon short he made it just one sentence long. He also liked to have a glass of wine, which he tells us is to be preferred over beer, beside him while he wrote.

During his early years at Cirencester Abbey Neckham is referred to as “Master Alexander” which may mean that he continued his work as teacher in the post of Headmaster of the Abbey School.

Why did Neckham choose Cirencester Abbey? Perhaps because he knew of it from conversations with Robert of Cricklade in the Augustinian House in Oxford. It has been suggested that he was aware that Cirencester Abbey had an excellent Library such as a scholar would need. The medieval emphasis on the importance of books is summed up in the aphorism: ‘A cloister without books is as a castle without an armoury.’

The value set on books is clear from such curses as this: ‘For him that stealeth, or borroweth and returneth not this book to its owner, let it change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with palsy and all his members be blasted. Let him languish in pain crying out for mercy and let there be no surcease to his agony till he sink in dissolution. Then, let book worms gnaw his entrails and when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of hell consume him – for ever.’

After its foundation, one of the first needs of St Mary’s Abbey in Cirencester was for books. The Augustinian canons borrowed works they wished to read and made copies by hand, with their own style of writing and initials. The English writer Bede (c.673–735) was among the most popular writers in the Cirencester library, who inspired the approaches of Robert of Cricklade and Alexander Neckham in examining the symbolism of the Bible. Amongst the books Neckham would have found in the Abbey Library was De templo (On the Temple). A note on the left-hand page says that the book was made in the time of Andrew, abbot of Cirencester (1147 to 1176), by Alexander, one of the canons, and Ralph of Pulham, a professional scribe. Unusually for medieval books, the binding is original, with holes showing it was part of a chained library.

It was at this time that Neckham wrote Corrogationes Promethei (The Teachings of Prometheus). “While ‘On Useful Things’ teaches basic Latin, this book is aimed at a more advanced level. The first part discusses the theory of grammar as one of the seven liberal arts, as put forward by ancient authors. The second part is a list of difficult words in the Bible, and was widely admired and reworked. The prior at nearby Malmesbury Abbey gave the book a rave review: ‘After that book came into my hands on the meanings or properties of words – or, if something of this sort should be said, published by the good master in an introductory way for the teaching of children – I rejoiced at the very sight of the prologue to such a point that at every word I was offering benedictory prayers for him.’ The irregular shape of its pages shows the scribes using every scrap of parchment that they could find.” [Andrew Dunning]

Neckham preached many sermons, copies of which were collected and are still available to us. They would, of course, have been informed by his theological studies and also his spiritual life centred on the daily recital of Psalms. It is not surprising, therefore, that he should produce theological works about the Psalms.

“Glosses on the Psalter is an edited version of Alexander’s lectures on the Psalms. The text is in large writing in the centre of the page, with his commentary in the margins. This layout was difficult to produce by hand, but was highly practical for teachers. This book was probably made in Cirencester, but the ten historiated initials with gold leaf are in an Oxford style. It was originally in two separate volume” [Andrew Dunning].

It was also in his time as Canon/Master Alexander that he wrote De rerum naturis (On things in nature). Subjects covered in this and others of his works included astronomy. ‘The sun is a hundred and sixty times and a fraction larger than the earth’. Neckham also wrote about plants including herbs which were the foundation of medieval medicine and grown in the Abbey garden. Both Herbals and Bestiaries were available at this time but Neckham seems to have implemented the new approach to scholarship and, from actual observation rather than received opinion, corrected many errors even omitting some of the more fantastical notions of such writers as Gerald of Wales (1188). He also suggested that gardeners should try to see if they could get plants to grow, another indication of Neckham’s encouragement of an inquisitive mind.

In 1213 Neckham produced Laus sapientie divine (The praise of divine wisdom) a versified version of De naturis rerum which shows his continued interest in scientific matters including the stars and the elements. Three years later, shortly before he died, Neckham wrote Suppletio defectum (Supplying defects or amendments …to Laus sapientie divine) in which he writes about birds and other animals and gives descriptions of trees, herbs and other plants.

Here he also reveals that the concern over the calculation of the date for Easter was still current: there are still, he says, ‘manifest errors in the vulgar (i.e. common) compotus’. ‘The love of knowledge’ he writes ‘is naturally implanted in the human mind. Hence it aspires to an understanding of it. It seeks out the cause of things’, reminding us of Neckham’s involvement in the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the new theological thinking.

Elected Abbot

Neckham was elected Abbot in 1213 in the presence of King John. He already had experience in Abbey administration as he had been appointed by the Bishop of Worcester to oversee Abbot Richard under whose Abbacy a Visitation by the Bishop and the Archbishop had revealed mal-administration. Neckham was also an ecclesiastical judge and was appointed as a papal judge. In civil matters he acted for King John in examining the rights of the Augustinian Priory of Kenilworth.

During 1208-1214 England was placed under interdict by Pope Innocent III when King John refused to accept the Pope’s nomination of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. An Interdict had great effect on the Church and the People; public services were banned and the appointment of new bishops suspended. It is a mark of Neckham’s reputation that he, along with his friend Peter of Blois and others, was used by the King to negotiate with the Pope. Royal records of King John’s reign include: ‘May 1213 – Henricus de Alemannia – 15 pence for taking some letters to Alexander at Cirencester.’

It was during Neckham’s time as Abbot that the Abbey regained some of its lost rights in the Seven Hundreds (the extensive area in the Cotswolds over which the Abbey had gained control) and also obtained the right to an annual market over the eight days of All Saints-tide. It is not surprising that administrative concerns meant that Neckham’s scholarly output now fell away. And yet it was as late as 1213/5 that he wrote his major theological work Speculum Speculationum (Mirror of speculations), set out in four books. The main thrust of Book One is to address the Cathar Heresy. In Book Four he discusses the subjects of grace and free will. One writer, R.M. Thomson, who edited a translation of the work (Oxford 1988), suggests that relieved of educational demands Neckham became ever more discursive in his writing, revealing his interest in both Platonic thought as well as his beloved Aristotle. It was not until Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) that the conflict between Plato’s philosophy and Aristotle’s was considered resolved.

Neckham also wrote in verse which was part of the 12th century interest in language stemming from the development in Latin scholarship. Swanson summarises this as ‘Words and their meanings – and implications – were basic to any attempt to comprehend the world.’

Towards the end of his life he wrote Corrogationes novi Promethei (New Teachings of Prometheus) a long and uncompleted work. The first part is concerned with the Monastic life. ‘The Abbot must be the teacher by precept and example. He must not be too anxious to fill the chests with gold.’ Did the experienced Abbot Neckham, one wonders, accept the need for an appropriate level of concern to secure sufficient gold?

In Part Two he writes of the need to avoid vices – which include becoming gloomy and the excessive use of candles, presumably for personal light rather than in the church. In the Third Part, Neckham writes of the ages of Man. ‘It ends’, writes Hunt, ‘with an elegy on the loss of youth.’

1215 is one of the most famous dates in history as the year of Magna Carta but for the ordinary Christian person at that time, that year was of much more importance as the date of the 4th Lateran Council in Rome. It was at this Council that many matters were decided which impinged on the ordinary person’s life: the requirement to accept various doctrines, including Transubstantiation developed from Plato’s notion of essence and accidence, and other dogmas and to observe certain practices such as receiving Communion at least once a year after Confession.

It is indicative of Neckham’s academic standing that he was summoned to attend the 4th Lateran Council and an indication of his favour with King John that the King ordered the Bailiffs of Dover to provide Alexander with a properly equipped and staffed ship for the voyage. However, it seems likely that Neckham did not actually attend the Council as he wrote to the Bishop of Worcester that he was too ill to undertake such a journey.

One scholar (Frank N Magill) summarises Neckham’s achievement thus: ‘Through his prolific writing in many fields, his teaching at several educational levels, and his active participation in monastic life as well as royal and ecclesiastical service, Alexander Neckham was important in transmitting and transforming the widening intellectual interests of the twelfth century into their scholastic form of the late medieval period.’

Alexander Neckham died at Kempsey in Worcestershire, a Manor of the Bishop of Worcester, in 1217 – which means that this year we not only commemorate 900 years since the founding of the Abbey but also remember the death of its most famous Abbot, 800 years ago. He was buried in Worcester Priory, now the Cathedral, where a brass plaque in his memory can be found, most appropriately, in the cloister.

In translation, it reads: ‘Wisdom suffers an eclipse. A sun is buried, which, while it lived, every branch of learning flourished. Neckham is dissolved into ashes. Had he one heir on this earth, his death would be less cause for tears’.

Acknowledgements

The ‘Manuscripts of Cirencester Abbey’ exhibition was mounted by Corinium Museum and thanks are due to the staff for their expertise. The display was sponsored by Soroptimists International: Cirencester District and the transport of the manuscripts was sponsored by Tanners, Solicitors of Cirencester. Four manuscripts were generously loaned from the Bodleian Library and Jesus College Oxford where they are permanently preserved. Dr Andrew Dunning, Curator of Medieval Historical Manuscripts (1100–1500) at the British Library, gave much valuable assistance. Amanda Hart at Corinium Museum encouraged the re-use of texts from its blog pages. All the above are warmly thanked.

Further reading

Clark, J.W. ed., 1897. The Observances in use at the Augustinian Priory of St. Giles and St. Andrew at Barnwell, Cambridgeshire.

Corinium Museum website: https://coriniummuseum.org/

Dunning, Dr Andrew 2016. Alexander Neckam’s Manuscripts and the Augustinian Canons of Oxford and Cirencester’, doctorate thesis at the University of Toronto, Centre for Medieval Studies.

Hannyngton, H. Notes on a 12th century mathematical manuscript from Cirencester.

Hunt R. W. 1984. The Schools and the Cloister. The life and writings of Alexander Nequam (1157–1217). Edited by Margaret Gibson, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Magill, Frank N. (ed) 1998. The Middle Ages: Dictionary of World Biography: Volume 2. Routledge and Salem Press Inc.

Salter H.E. ed., 1922. The Chapter of Augustinian Canons. London. Canterbury and York Society.

Swanson R.N. 1999. The twelfth-century renaissance. Manchester University Press.

Welsford, Alan ‘The Library of St Mary’s Abbey, Cirencester’, Newsletter of Cirencester Archaeological & Historical Society, no 17, June 1975, pp.4-12.

Welsford, Jean 2010. Cirencester: A history and guide. 2nd edn revised Alan Welsford. Amberley.

Wilkinson D. and McWhirr A. 1998. Cirencester: Anglo-Saxon Church and Medieval Abbey. Cirencester Excavations IV.

Image 5

Image 4

Image 6

Illustrations, rear cover

- Ralph de Pullham is possibly the earliest known secular peripatetic scribe/illuminator. Images of Oxford, Jesus College, MS 62 and 94 are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence, by kind permission of Jesus College, Oxford. Photographed by Andrew Dunning.

- The medieval manuscripts on display in the Corinium Museum, January-May 2017 (image: David Viner).

- The annotations to this manuscript may well be by Alexander Neckham. Jesus College, Oxford, MS 94, fol 5v, Neckham’s Gloss on the Psalter.

NEWSLETTER No 63 for 2017

The Newsletter serves as an update and archive of various research and local activities and submissions are always welcome. Contact: dandlviner@gmail.com

The views expressed in the Newsletters are those of the contributors and/or the editor in each case and are not necessarily those of the Society.

The Newsletter (and Annual Report) first appeared for the year 1958/59. An archive set of all these publications, plus the four editions of Cirencester Miscellany containing longer articles on local history, is held in Gloucestershire Archives under the reference number D10989, where members and other enquirers are welcome to consult them (www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/archives).

Cirencester Archaeological & Historical Society is a registered charity (No. 287289)

August 2017