Cirencester Building Studies

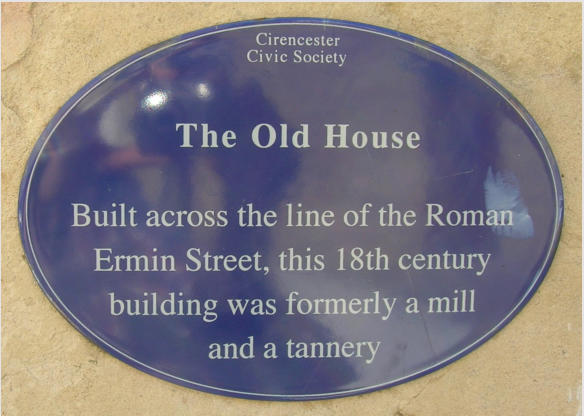

The Old House, Gloucester Street,

Cirencester

By Rosemary Burton

Almost the only thing we had against our house on first acquaintance was its name – almost a nickname: ‘The Old House’ … but this has since been justified.

The first reference to the building is as “The Mill on the Gildenebrigge” in 1317 – it appears to have been a small grist (or coarse) mill for animal feeding stuffs, in use at a time when the Abbey forbade all private mills, and probably working then, as frequently later, in conjunction with Stratton mills, catching the water as it entered the town and divided to serve the Barton Mills on the right, and continuing straight up (or rather, down. Ed) Gloucester Street, then St Laurence Street, to St Mary’s Mill by the Abbey Gate; and at a later date round to the New Mills, back on the main stream after it joins up again below Golden Farm.

The most obvious remaining portion of this mill is the old wall right on Gloucester Street, which formerly continued further towards the bridge, with a number of buildings round it; and a small dwelling house, of which there are still traces of a downstairs living room, with a probable bake-house adjoining (the miller’s wife’s perk?) and over the living room up a short stair, a family bedroom, with door through into the mill itself. Also, and accessible only from outside, was a bothy for the men, rather comfortably situated over the bake-house. The low cottages opposite are very likely the original ‘drowners’ cottages, where dwelt the men responsible for keeping the water meadows in order, to supply the mills.

After the Reformation, it may well have fallen into dis-use, as its use was not longer enforced; and also with the upsurge of private enterprise in Elizabethan times, better milling machinery was produced, which could do the job and utilise the power, so that fewer larger mills could do the job more efficiently (how familiar this sounds!). However, by 1615, it is once more a going concern and let to Henry Russell, though the property by now of Richard George of Baunton. In his Will, made in 1615, he lets the property in the care of Henry Russell, with a rent charge of £3 a year on it, to pay for the apprenticing of a local boy.

Subsequently, it appears to have been involved in the Battle of the Barton, on February 2nd 1642, when Prince Rupert, ‘drawing neere’ the town from the west and south, came across the Park and attacked the Barton Farm, where the Royalists were ‘valiantly entertained’ by the townspeople.

The Earl of Carnarvon, supporting the Prince, approached from the north and north-west (down Gloucester Road and from the Whiteway) and seeing the Barton fired, sought to enter from the north side and there was a ‘sore charge’, and the townspeople ‘yielded not till the enemey having entered the town by now on their other side, was on their backs.’ The place may well have been damaged in this encounter, and certainly the next we hear of it, it has had a good deal of work done to it – it has now become the town tannery, and no doubt quite a prosperous one, with vastly increased horse traffic, and all kinds of harness, as well as numerous domestic uses, such as ‘black jacks’, well buckets, and shoes, not to mention the military equipment for Marlborough’s wars etc.

Situated on the edge of the town (rather more pleasantly!) with plentiful water supplies, and right on the road for the wagons both to bring skins and remove hides, fairly near the various button factories, and handy for local supplies of tallow, the tanner and fell-monger thrived. By 1715 he was in a position to modernise the house completely, putting a splendid fire-place in the parlour, an oak staircase up, with bedrooms either side, and a separate kitchen downstairs, with a small courtyard in front, and beside a door giving on to the street outside, his own office with a hatch into the tanyard itself.

Onto this house Mrs Rebecca Powell, acting as successor to the George fortune, fixed a further term of one thousand years for the payment of three pounds annually for the apprenticing of a pupil of the Blue Boys’ School, with Joseph Harrison the vicar and Sir Thomas Atkyns of Sapperton as ‘trustees’, and named the tenant as Walter Naish. He was succeeded, perhaps though marriage, by William Slatter, whose children, Mary (1800) and William (1801) were born here. Mary married a member of the Vaisey family, and went to live in Stratton, and various members of the family ran both Gloucester Street and Stratton mills at this time.

Having prospered over a further period, and it having been previously decided to alter the school charities from depending on rents to having capital sums (producing income for the same purposes), the whole property was put up for sale in 1821, viz. dwelling house, outbuildings, fell monger’s premises and counting house, and was then bought by Thomas Slatter.

Employing craftsmen then fairly available from the considerable building confraternity in Cheltenham, the house was completely modernised, using most of the existing outbuildings, closing the foot-passage leading directly up Gloucester Road from Gloucester Street, putting the road behind the house now that the river no longer ran down beside the street, and thus making a pleasant garden at the side.

For a time known as ‘Magnolia Lodge’ (although no one recollects what happened to the magnolias), the house had various tenants after the Slatter family left it, the best known of whom was Mrs Allen Harker, whose well-known and well-loved novels of her day were written in and frequently placed in ‘The Old House’.

In the Second World War, it not only gave up its iron railings for munitions, but it was actually machine-gunned, losing several windows! But it did not seem unduly perturbed, and now we feel that it can probably lay as good a claim as most to being known as ‘The Old House, Gloucester Street’.

Please Note: This house remains a private dwelling and is not available for viewing.

Editor’s Afterword: for a more recent study of Cirencester’s watercourses, which refers to the above survey in its wider context, see the essay ‘Cirencester: the interpretation of streams’ by Richard Reece (with illustrations by Peter Broxton) in Newsletter 53, Spring 2011, pp.1-8

This article was originally published in the Society’s Annual Report and Newsletter No. 10, May 1967-May 1968, pp. 9-11, and reprinted with additions in Newsletter No. 54, Autumn 2011, pp.08-12 as ‘Two old Cirencester houses’.