From Newsletter 53: 2011

Cirencester: the interpretation of streams

by Richard Reece and Peter Broxton

Water, up to the 18th century meant power – motive power, mechanical power and even political power. Its energy could be harnessed for many productive purposes, but the only examples around us in Cirencester seem to be a majority concerned with grinding corn and a minority concerned with yarns, materials and fabrics. In the Stroud valley, of course, the balance is just the opposite.

This suggests to me that any discussion of water courses around Cirencester has to take into account the known and suspected water-driven mills.

These demand a flow of water, as constant and powerful as possible, and an escape for the water to get away when it has done its job. To increase the power of the water it is a good idea somehow to back up the water upstream of the mill to create a head of water which can be sent through the mill when desired or otherwise allowed to run away down an overflow. The background to all this received a very good introduction when Robert Walls published his study of Langley’s Mill (Walls 1986, 4-17).

Parting of the ways for the Daglingworth Brook at the Gloucester Street bridge, where the Barton Mill route (and thence Gumstool or Gunstool Brook) goes under the bridge; via the sluices the Abbey Way route goes off to the left. Seen here on 23 August 2014 when the route under the bridge was dry and overgrown. The significance of this location is discussed in detail in the article. Maintenance of water levels throughout the year remains a contentious local issue

He suggested that his work was limited to the one mill but in fact he provided a much wider study. All I want to do here is to extend the study back a little in time and to ask some more general questions.

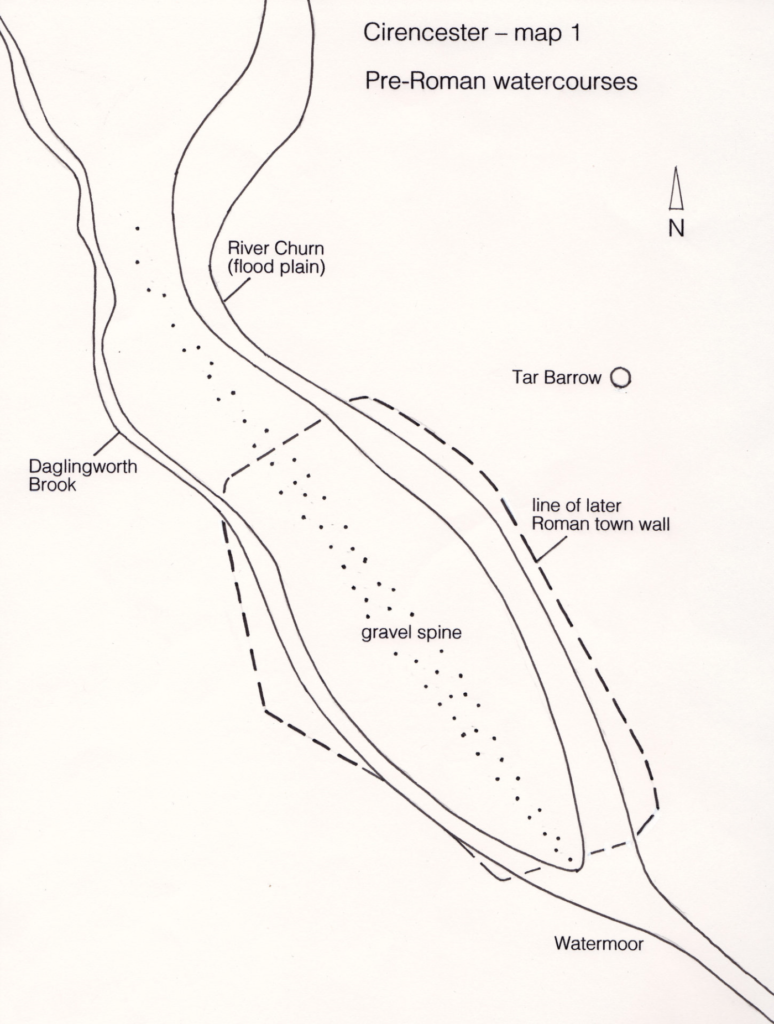

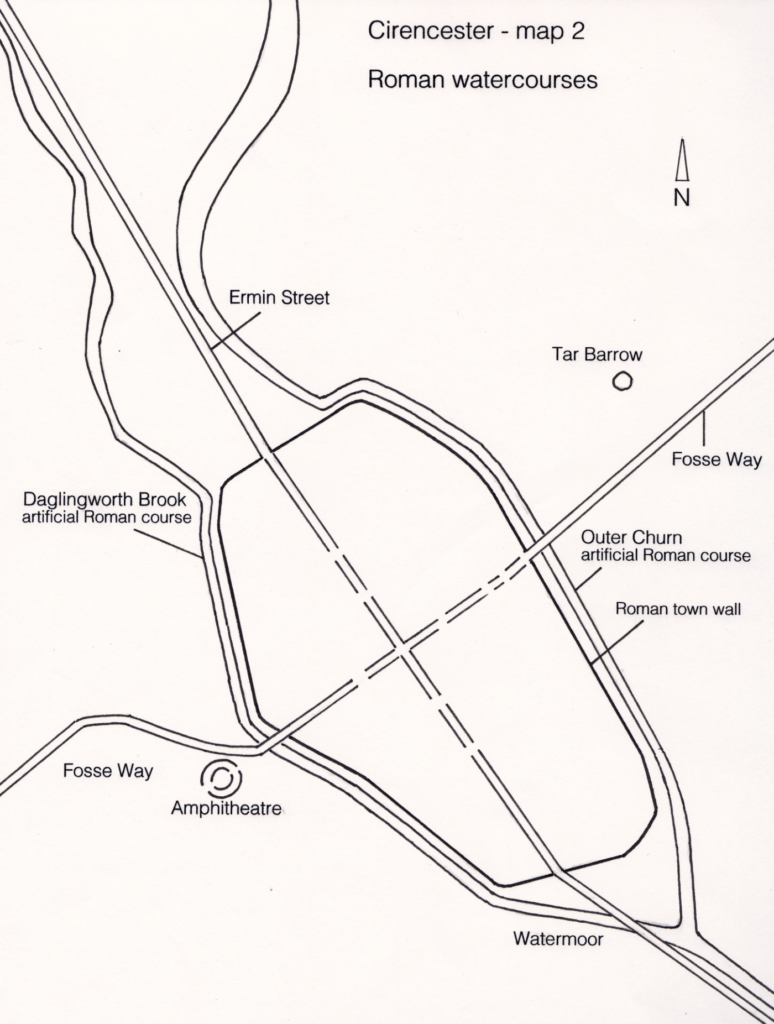

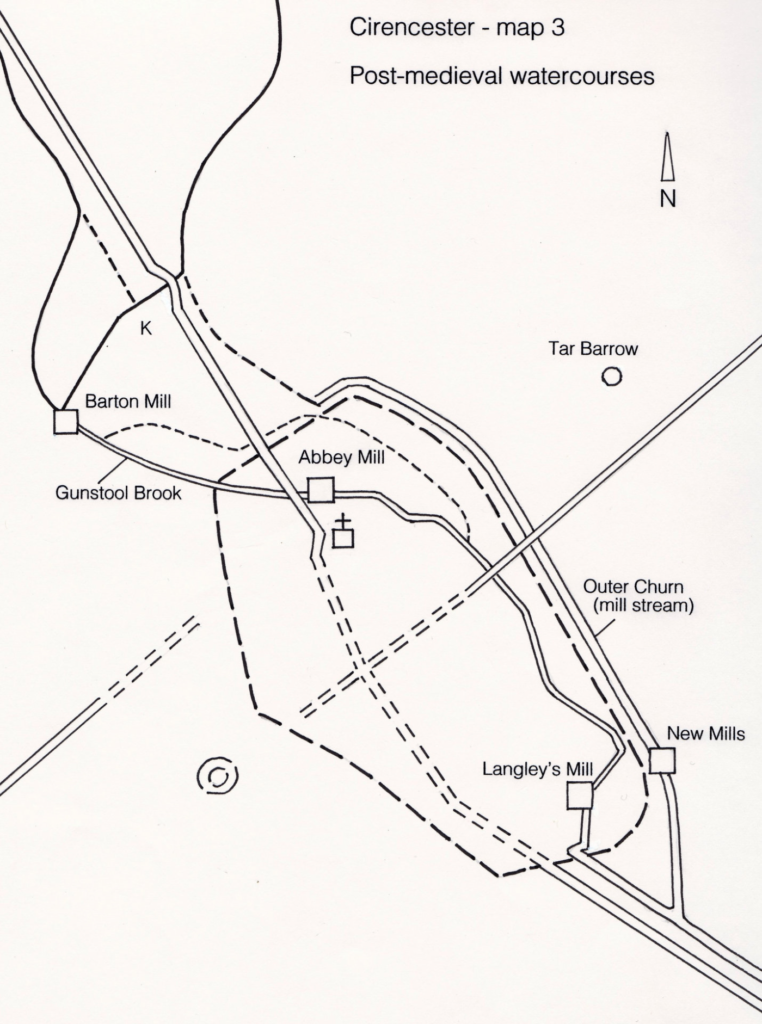

The incoming water courses are the Daglingworth Brook and the River Churn. Map 1 suggests the natural course of each, prior to the Roman intervention illustrated in Map 2. Using modern names and locations the mills available for study (Map 3) seem to be Barton Mill (BM), New Mills (NM), Langley’s Mill (LM) and the Abbey Mill (AM) at the junction of Gosditch Street and Dollar Street. For the moment I have relegated “the mill at the Gildenbrigge” to the end of the discussion as a “Problem for the future”.

Taking the mills and the streams in the simplest possible way it seems clear that the Daglingworth Brook flows direct to Barton Mill. In an artificial course it then continues via the Swimming Baths (where it becomes Gunstool Brook) and behind Coxwell Street to flow under the hump at the Gosditch Street/Dollar Street junction to power the former mill there (AM). This was the situation by 1230-50 when Nicholas Pilet gave a piece of land between Abbots Street (by common consent Coxwell Street) and the stream leading to the mill within the Abbey (Ross 1964, document 282/139) — “que terra jacet inter uicum abbatis et cursum aque que uadit ad molendinum quod est infra abbaciam”. After this it flowed on to clear the effluent from the kitchen and reredorter of the Abbey and thence escape to wander through Watermoor.

The natural course of the Churn is to flow almost to Gloucester Street, come up against the gravel spine on which the centre of the town is built (Map 1), and turn away between the back of Gloucester Street and Abbey Way through what were once St John’s Meadows. From there the continuation of the natural course would be to take the route that it took, to many people’s discomfort, in the floods of 2001 into the Abbey Lake and out through the lowest land beside The Waterloo and thence behind Purley Road

But this topographically natural course was blocked in the Roman period (Map 2; note also comparable control of the Daglingworth Brook). A new, artificial, higher course was dug along Grove Lane just outside the Roman walls, and the water was not allowed to escape till it rounded the City Bank and fell into Watermoor. This gives the site of New Mills a prime head of water as the artificial stream could be built up, ready to escape with force back to its natural level. Robert Walls made clear the importance of the Furnes Hole which allowed some of the high level Churn to run off into the City Bank and so feed Langley’s Mill, and early maps do suggest that the high level water was also led off somewhere in the middle of Beeches Road further to the north. Both these courses add to the flow of the Gunstool Brook/Abbey Stream which could have provided a decent head of water for Langley’s Mill. All traces of the original course of the Abbey Stream have been lost through the setting out of the former Grammar School Field and the building of the (disused) railway embankment, but survive on the 1795 and 1835 maps. The overflow from the upper level under Beeches Road is well within living memory as a stream through the rock garden of River Court – now a block of flats. The Furnes Hole is still visible in City Bank.

There are some observations which need to be made at this point. Barton Mill is clearly built to use the water from the Daglingworth Brook. If it had been built to use the Churn water it would have been nearer the Churn. I say that because the present cut from the Gloucester Street bridge down to Barton Mill has an almost level bed. In the summer there is hardly any movement in the water and it is almost impossible to tell which way the flow normally goes. This strongly suggests to me that the cut is artificial and intended to lead off some of the Churn water for Barton Mill. At the Gloucester Street bridge the greater drop is into the Abbey Way course and it is only by regulating the sluice gates that the Barton Mill cut gets any Churn water at all. Without those gates all the water, for most of the year, would follow Abbey Way. This means that if the Churn brings down a lot of water a strong embankment would be needed to divert it all to Barton Mill. In fact the Abbey Way course must always have acted as an overflow even when the main idea was to help power Barton Mill. The Gloucester Street cut only had to run from the bridge to the end of the Mill Pound – I suspect. In wet weather you can see a relic of Daglingworth Brook seeping through the water meadow to join the Mill Pound at K (Map 3). The present course of the Brook directly to the Mill is presumably an overflow for when the Mill Pound had filled up to an optimum level.

So when was Gloucester Street cut to divert Churn water to Barton Mill? I am reasonably sure that it was not done in the Roman period. The idea then (Map 2) was to lead the Churn round the London facing walls and Daglingworth Brook round the Bath facing walls. The two streams were divided by the gravel spine which presumably was built up by the action of the two streams. The spine runs from the Gloucester Road, down Gloucester Street, through the market place, is very marked at the Tower Street/Lewis Lane junction, is a marked bump in King Street, and makes for the Silchester gate and the Old Cricklade Road.

At the point of the cut itself Gloucester Street had to be diverted. The houses built on the line of the kink are probably no older than about 1600, most of them later than that though the part of “The Old House” which blocks the line of the road is difficult to date. The original road line of Ermine Street coming from Gloucester is still marked in the field beside the garage by a line of lime trees. If the cut had been Roman then the roads would still be on the Roman alignment and a Roman bridge would have been replaced from time to time by later bridges. The diversion can hardly have been caused by the collapse of a bridge because it would have been necessary to demolish properties in order to make the major diversion, in order to repair the bridge and the demolition and compensation would have been a far greater undertaking than simply putting a temporary wooden bridge over the stream while the stone bridge was repaired beside it. The kink must presumably have been caused after the Roman period but before the end of the medieval period as the only way to make a cut through the gravel spine. Before the road was diverted a dry cut was dug below the new course of the road; over this dry cut a bridge was built and the diverted road led over it. Once this had been done further cuts could connect up the Churn and the Barton Mill Pound, and Churn water could be diverted to the Mill.

After working the mill all the water could escape towards the town. But if the full force of the Churn was to be diverted through Gunstool Brook to work the Abbey Mill and clear out the reredorter it would cause major floods almost every winter. Gunstool Brook could only be made by cutting the gravel spine again at the Dollar Street/Gosditch Street junction. It would only be made to service the Abbey and this presumably dates it. The opportunity was taken to harness it to a mill right beside the Abbey. To avoid flooding Coxwell Street cellars every year an overflow was needed when Churn water was sent to Barton Mill and this must be when the cut for the extra stream going between The Mead and Powell’s School, through the gravel spine at the Powell’s School hump, under Spitalgate Lane with another hump, and into the Abbey Lake was made.

The sequence seems quite reasonable when set out as follows:

Map 1. Before the building of the Roman town the two streams ran either side of a gravel island until they met in a marshy swamp at Watermoor. Recent (December 2010) geophysical survey in the Abbey Grounds produced something which looks very like the original course of the Churn.

Map 2. In the Roman period the Churn and Daglingworth Brook were both canalised round different sides of the walls to remain separate until they met to the SW of the town towards Preston and Siddington. It seems very likely that their power was harnessed at some time to drive corn mills but as yet there is absolutely no evidence for this. There is also absolutely no Roman sign for the other function of water – to supply the baths and flush out any sewers. Neither at present have any firm evidence in Corinium though fanciful suggestions have been made.

In the Domesday survey Cirencester has three mills. It might be tempting to assume these are the three that we know towards the end of the 15th century but this would be to assume the Abbey Mill existed before the Abbey. Perhaps we should count Barton Mill, the predecessor of Langley’s Mill and one, now lost, on the outer course of the Churn – perhaps even a predecessor to New Mills. The perfect site for this would be the sudden (present) drop in level as the Churn rounds the corner, coming from Stratton, and flows fast down beside Abbey Way. A mill on either side of the stream at the Abbey Way bridge, NOT the Gloucester Street kink bridge, would always be sure of a powerful head of water above the mill and a good escape route for the water after use. Rudder (1800, 138) had heard of a former mill 400 yards upstream from Barton Mill and I prefer this, actually on the course of the Churn, rather than any connection with the Old House (see below)..

All this assumes, contrary to what Mr Walls assumed, that the outer course of the Churn, from Gloucester Street bridge, along Abbey Way, and beside Grove Lane is the natural course of the Churn which was at some time diverted after the Roman period.

The Abbey appears only to have had one mill of its own at first – this would be the Dollar Street/ Gosditch Street mill (AM). Langley’s Mill was not owned by the Abbey, and though Barton Mill is always described as “by the Abbot’s Barton” (= Grange) it seems to start off on an independent course, later given to the Abbey. When the Abbey decided to divert water that had already driven the Barton Mill through the town to flush out its rubbish perhaps it realised that it would be sensible to use the water as mill -power first. This would account for the odd placing of the Abbey Mill mill on the gravel spine near the centre of what was presumably a built up area. Perhaps this helps to explain the diversions, sluice gates, and later court cases so well described by Walls.

If, when water was diverted to the Abbey, it was to flow naturally it had to come from Barton Mill. One walk in the Abbey grounds will demonstrate that any water from the Churn would have to flow uphill to the Abbey. So things might have continued – and at this point I drift into speculation – if the Abbey had not become greedy. The only way to get more water into the Abbey mill and through the Abbey was to lead more water through Barton Mill and I suggest that it was at this point that the flow in the natural course of the Churn was at least partly diverted, if not cut off, so that most or all of the Churn water went through the new Gloucester Street cut to Barton Mill. Thence it flowed through Gunstool brook behind Coxwell Street to the Abbey. But the full force of the Churn in winter would be too much for this course alone, hence the Powell’s School overflow, and in emergency, the natural Abbey Way course. When the fulling mill was built at New Mills there was a dilemma as to how much water should go through the town and how much should go straight to New Mills. This uncertainty became worse when New Mills stopped up the leat to Langley’s Mill and Mr Walls’ litigation ensued. Eventually, sometime around 1800, further litigation led to the fairer division of water – as described by Walls – and the natural course of the Churn was put back into full operation with only a portion of Churn water making its way through Barton Mill.

If only Corinium had been built on the site originally intended for it by the Roman planners and surveyors (Reece 2003, 276 – 80 for details) all these problems could have been avoided with the Roman and medieval town on the slope of Tar Barrow field and the streams down in the marshy valley bottom canalised as necessary to drive a selection of mills. But the ceremonial centre, of which Tar Barrow itself is the only obvious sign, meant that the town went in very much the wrong place, the narrow gravel spine, and we are still trying to sort out the problems of the streams.

Problems for the future

The water courses on the Bath side of town after the Roman period still present many problems. One such problem is the feeder for the 18th century canal. At present it disappears under the Cecily Hill Barracks and is never seen again apart from manholes in the lawn on the Park side of the Mansion. I hope someone else will work on this in the near future.

It is just possible that what I have called the Abbey Mill, powered by the Daglingworth Brook via Barton Mill could pre-date the foundation of the Abbey. This would connect it with the Saxon church and the college of Canons. The historical and topographical problems are very much against this but only archaeology could give firm dates. On the topographical side, to divert a stream through the middle of the town and dig deep through the gravel spine just in order to put a mill near the Saxon church, is a total waste of effort when several watercourses running more or less naturally are within easy reach. On the historical side, as outlined by Dr Evans (1989, 107-122), the clerical establishment of the Saxon church was probably never substantial enough to make, support or even need such works.

This diversion and change of use for the Daglingworth Brook after Barton Mill (by about 1230, see above) may be connected with the gift by Geoffrey the Clerk of Stratton of Letherwell and its water to the abbey for their lavatorium – water provision, washing and flushing (Ross 1964, 235/225). The gift is dated to the first half of the 13th century, so well before the date we know for the stream running behind Coxwell Street. After this there are other gifts of land beside the water which could possibly act as easements for the diversion of the water and its re-use. This aspect needs more work on the very tangled subject of water rights, new uses, and diversions which cannot be dealt with here.

The mill on the Gildenbrigge to which Mrs Burton referred in her discussion of The Old House in Gloucester Street, with the Slatter family as earlier occupants, poses problems which need much more detailed discussion than is possible here (Burton 1968, 9 – 11). Fuller in his paper on the Register of the Parish Church Lady Chapel (Fuller 1893 – 4, 322) found a reference (folio 7.a) to “two messuages at Gildenbrigge which are upon the running water”. In the Abbey Cartulary the Gildenbrigge occurs in several documents concerning the transfer of tenements (Ross 1964, documents 296 ff., 270 – 5). Fuller interprets this as “the Gildenbrigge was the ancient name of the bridge at the top of Gloucester Street, over the Churn, as it runs down the mill stream to the Barton Mill, then known as the mill of Richard Clark”. Documents 296 – 302 do indeed refer both to mills and millers but so far as I can see those mills are not necessarily AT or ON the Gildenbrigge. I think Mrs Burton’s statement relies on a sentence in ‘Cirencester Present and Past’, by W. Scotford Harmer (1924, 320): “a site near the Gilden Bridge now occupied by Barton Villas, and afterwards in the possession of the Vaiseys, and later of the Slatters”. This clearly needs more detailed work, and better references, to sort it out.

Finally there is the water course referred to by many writers from Leland onwards but most easily quoted from Rudder (1800, 137 – 141, a reference kindly supplied by Linda Viner). This was seen to run along Gloucester Street, Dollar Street, Cricklade Street and out into Watermoor. Because so much of this line runs along the highest points in the town it cannot be a natural watercourse and the simplest explanation is that it is a channel dug to provide an open sewer through the town flushed from water drawn from the Churn by the top of Gloucester Street. As Leland himself wrote, in a variant copy of his main work (Latimer 1889 – 90, 228),

Be lyklehood yn times past Guttes were made that Partesof Churne Streame might come thorough the Cyte, andso to returne to theyr great Botom.

Because it was said to have run along Gloucester Street (outside the Roman town) and Cricklade Street (not on the line of a Roman town street), it cannot have Roman origins and might be an early example of Municipal Sanitary Engineering (or might not!).For later studies (2018) by Richard Reece on this topic see: Webnotes: Cirencester Streams

References

1795 Plan of the Borough Town of Cirencester, surveyed by Richard Hall & Son.

1835 Map of Cirencester, surveyed by John Wood.

Burton, R. 1968. ‘The Old House … Gloucester Street’, Cirencester Archaeological & Historical Society Annual Report and Newsletter, 10, 9 – 11

Evans, A.K.B.1989. ‘Cirencester’s Early Church’, Transactions Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 107, 107-122

Fuller, Rev E.A. 1893 – 94. ‘The Register of the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Parish Church of Cirencester’, Transactions Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 18, 320-331

Harmer, W. Scotford, 1924. ‘Cirencester Present and Past’, in W. St. Clair Baddeley, A History of Cirencester, 309 – 328.

Latimer, J. 1889 – 90. ‘Leland in Gloucestershire’, Transactions Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 14, 221-84

Reece, R. 2003. ‘The Siting of Roman Corinium’, Britannia, 34, 276 -80

Ross, C.D. (ed). 1964. The Cartulary of Cirencester Abbey, 2 vols.

Rudder, S. 1800. The History of the Antient Town of Cirencester.

Walls, R. 1986. ’Langley’s Mill, Cirencester’, Cirencester Archaeological & Historical Society Annual Report and Newsletter, 28, 4-17

Editors Note March 2018 A new report sponsored by Cirencester Town Council discusses these issues further:

Young T P “A geophysical Report on Cirencester Abbey Grounds, March 2018” available here

A delightful walk alongside the Barton Mill Stream between Gloucester Street and

the mill (8 July 2009).

Photos David Viner